The dimensional divide: effective communication in 3D space requires a 3D solution

A look at the past

The year is 1983. The age of mass interconnectivity is dawning. Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) debuts, and the concept of electronic mail is born. Suddenly, you don’t need a pen, paper, and stamp: just an email address and a computer. Yet users still crave real-time, text-based communication – something more immediate than email.

This desire drives the creation of the first mass-adopted text-based communication technology: Internet Relay Chat (IRC), which launches just five years later in 1988. For the first time, people can communicate with each other through text on a screen. The ability to chat with anyone, anywhere, in real-time is a historical first.

Technological innovation has always outpaced expectations, and 1993 is no different. CERN releases the World Wide Web source code to the public, and there are just 500 known web servers. By the end of 1994, just two years later, an estimated 10 million people are using the Web, and there are 10,000 servers. By 2005, just over a decade later, one billion users are surfing the World Wide Web and every five years after that, another billion people add to that count.

The Information Age is here – and it’s here to stay.

An early look at the World Wide Web.

A look at the present

Today, consumers and businesses alike are spoiled for choice when it comes to communication: smartphones are always within reach, laptops allow people to work on the move, and even flights now offer WiFi, some as standard. Communication has never been so readily available, and yet the way we use it has, more or less, remained the same: text, images, and video on a flat, two-dimensional screen.

We’ve all mastered communication in 2D, but the irony is that even when we’re creating spatial content in 3D, we’re forced to compress it into a 2D screen format.

If you’re a 3D artist, you’ll have experienced this frustrating workflow… You’ve just created some complex 3D content, you start recording a 2D video, moving around the content to showcase it at different angles, and then you shoot the video over to the team to take a look. The team provides feedback, be it changes to the content itself or its position within the world, and after a clumsy, hard-to-follow thread of messages, you fine-tune your creation. Rinse and repeat.

Even as our technology advances into virtual, augmented, and mixed realities, we still rely on those same 2D tools to communicate within them. At Magnopus, through OKO – our suite of interoperable apps built for creating and running cross-reality environments – we saw a unique opportunity to solve a problem that has historically been silently problematic: How can we provide people with the means to effectively and efficiently communicate with others in a 3D context?

Laying the foundations

In 2022, we realised that we had already started encountering these sorts of inefficiencies when communicating in the context of OKO. From the valuable feedback we’d gathered from third parties, our users, and our own internal teams, we concluded that OKO needed a built-in communication tool to enable better collaboration. We saw it as an opportunity to solve some of these unique and historic challenges for OKO and, by extension, our users.

Despite that, we still needed some groundwork to build on: a simple user interface we could extend while ensuring we weren’t just offering an embedded version of the same tools already on the market.

Comments

Our first implementation of Comments was a proof-of-concept, released in 2023. It wasn’t well-suited to our existing infrastructure, nor was it designed to be – this was new ground! The feedback we gathered, however, was the most important thing. It’s impossible to present the functionality of a feature via text for the purposes of gathering feedback, and so our first prototype served well.

Initially, Comments were simple. They consisted of a title, a body, a timestamp, and the author, as well as offering a button to teleport a user to the position from which the Comment was authored. For us, this was a good start as it served as a prototype we could iterate over and gather feedback from. It was, however, missing something key: it didn’t foster the collaborative energy we envision within OKO, and, ultimately, it was too similar to the existing communication tools on the market.

And so, in 2024, having gathered all of the feedback from version 1.0, we decided it was time to begin the next iteration of Comments. I won’t dive into the feedback in detail here (I’ve been told there’s a limit to how much people will read nowadays), still it demonstrated some key areas to focus on: design, reliability, functionality, and responsiveness.

And so we focused our efforts on answering a question we’ve already asked in this article: How can we effectively and efficiently communicate and collaborate with others in a 3D context, and more importantly, how can we make that a great experience?

Initially, we considered adding the ability to add screenshots, images, or videos to give readers of the Comment some extra context to understand them. But, after consideration, this was too similar to existing tools that already offer built-in conversations with file upload functionality.

And, in the context of OKO, it didn’t really make much sense.

When large groups collaborate, it typically results in large-scale changes with added complexity. But that led to problems as communication relies on text, even when the ability to upload images or videos is available. What if someone comes along and moves the object? What if it no longer even exists? How do you annotate something, like you would on a screenshot, that will very likely move around or change in appearance?

Annotations

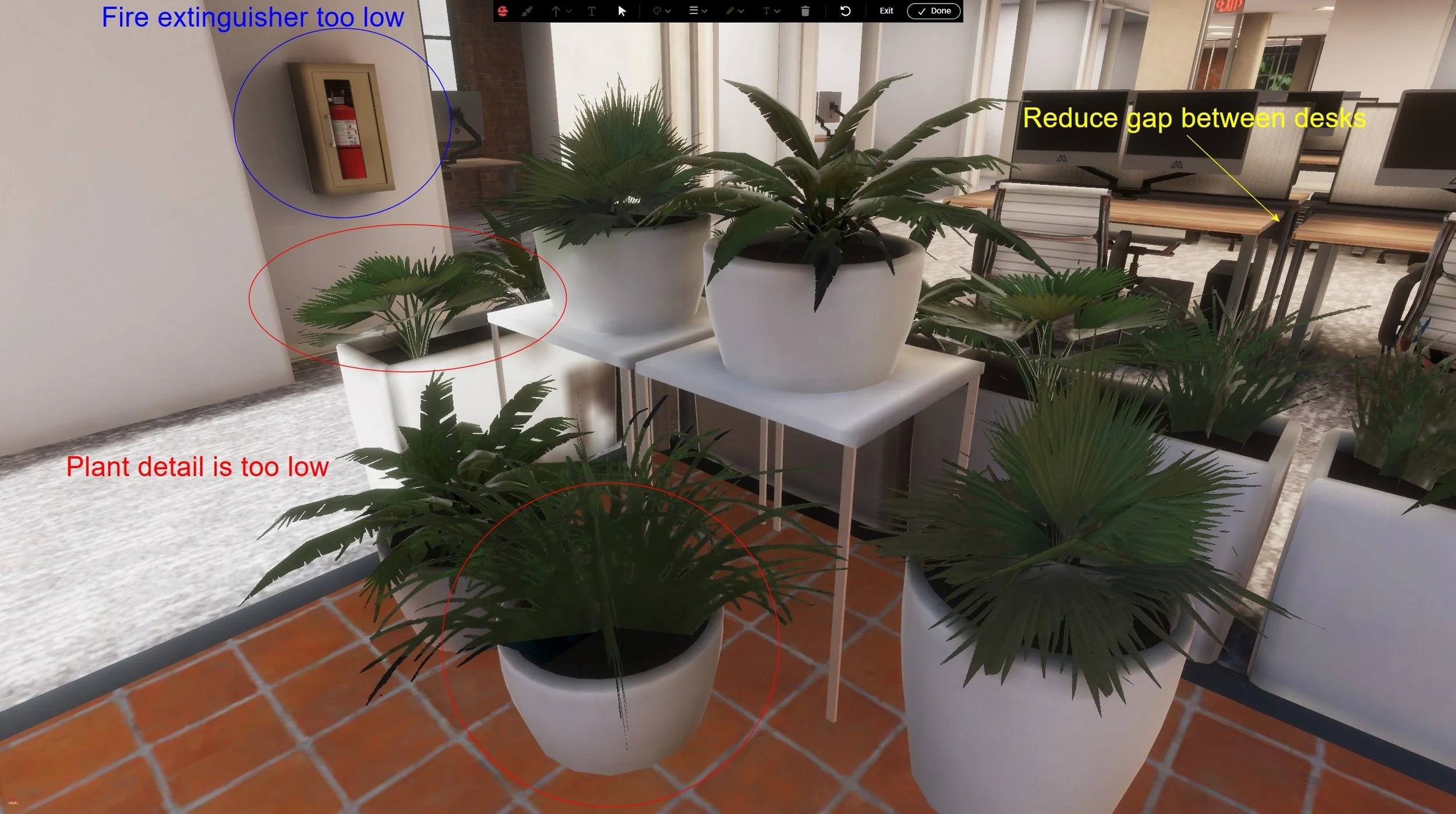

After Comments, we were finally at a point where we could tackle the hard part: 3D spatialised communication. After considering screenshots and/or videos, we decided to do something quite radical: a second, static camera with built-in drawing tools in the UI. Painting on a camera frame, if you will. Annotations was a fitting name for the feature.

We did face one key question, though: if a user adds an Annotation and the spatial context changes, how do they know what it was referencing in the first place? To solve that, we decided to fall back to something we’ve discussed a lot already – screenshots. The thumbnail for any Annotation is a screenshot of the spatial context the author saw at the time of authoring the Annotation. We’re not so anti-2D after all!

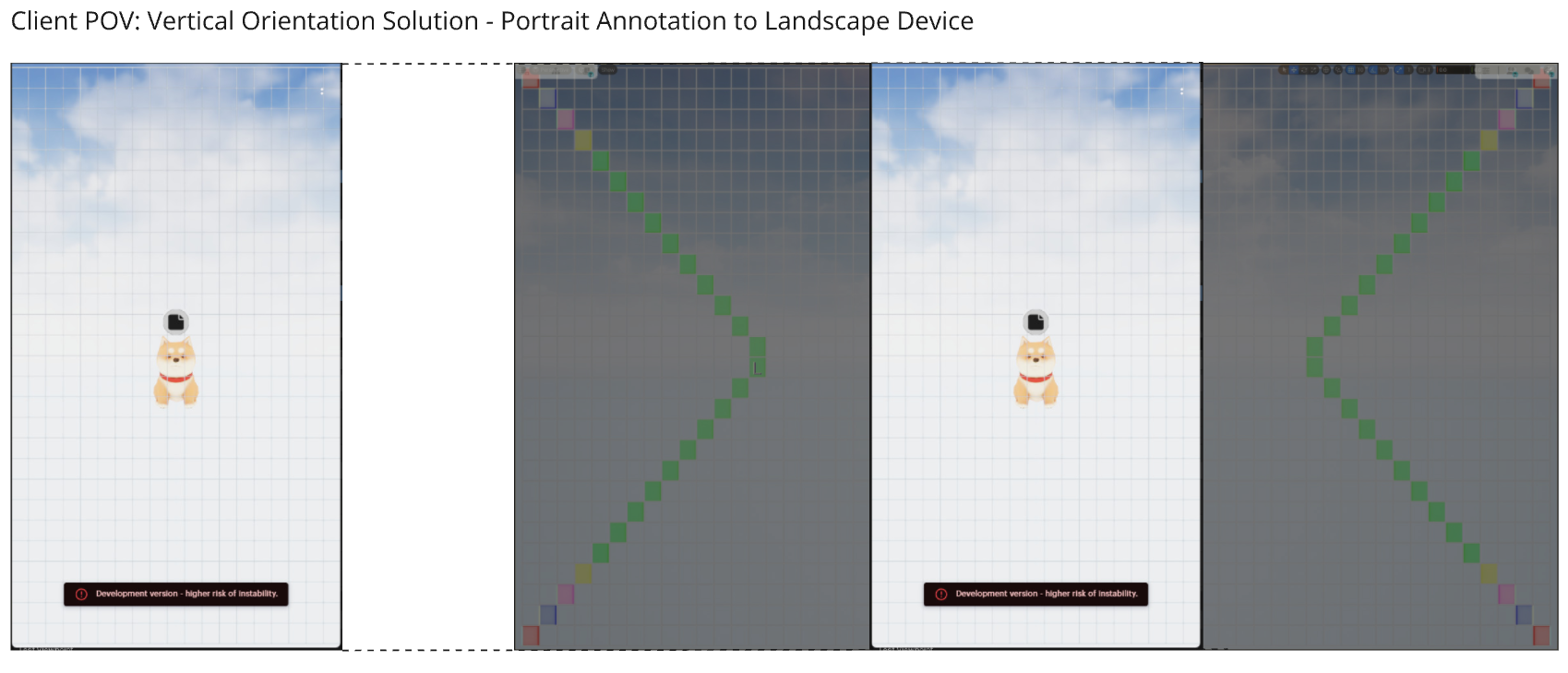

Our main problem was one of our own (and intentional) making. OKO supports almost any device – from smartphones to headsets to desktop computers and laptops. We had to account for infinite screen resolutions, aspect ratios, and field-of-views (FOVs). Handheld devices, such as smartphones, vary in resolution and aspect ratio and can’t be changed. In contrast, desktop devices are totally configurable and dependent on external hardware such as monitors. In addition, the engines we build on, such as Unreal Engine 5 and Unity, offer fully customisable FOV settings, with UE5 using horizontal FOV and Unity using a vertical FOV.

All of these variables were important to control, accurately convert, and store as part of each Annotation to ensure that when one user views another user’s Annotation, they both see the same thing. As with Comments, we began the long process of testing these variables on multiple devices with different settings to see whether we could accomplish this.

We now had the data that we needed to collect and store:

The author’s coordinates at the time of creation

Their aspect ratio

Their vertical FOV

A screenshot of the spatial context at the time of authoring for comparison

Early solution architecture.

Despite the complexities, this unique approach solved several problems that screenshots or videos have historically had.

Firstly, if one user is using different settings from another, then we can display an accurate representation of the 3D context of the Annotation. With videos or screenshots, things can change massively due to user-specific or device-specific settings, making it challenging to understand exactly where they were captured in a spatial context, especially in larger areas.

Secondly, if the context of the video or screenshot changes or is moved around, then they’re no longer accurately represented within a spatialised context. With Annotations, this change is immediately visible because the thumbnails show a before and the Annotation, when viewed, shows the after, leaving no room for ambiguity.

Finally, the long-discussed problem we solved: text is simply not very good at describing 3D spatial context. Annotations leave no room for ambiguity. When combined with Comments, Annotations really come into their own: this is the author, this is what they want, this is what they saw when they wrote it, this is what they drew, and this is what it looks like now.

For over five decades, we’ve relied on text, images, and videos to convey complex ideas on screens. With Annotations, we’ve challenged the status quo and developed a unique solution that moves conversations and collaboration inside of the experience rather than outside of it. This fundamentally improves the speed, efficiency, and effectiveness of spatial creation – from digital twins to virtual concerts and beyond.

Example annotations use case.